In Company with the Devil

There are almost a hundred places that ‘belong’ to the Devil in Britain, such as the

Devil's Punchbowl (Surrey),

Devil's Dyke (Sussex and Cambridgeshire) and so on, and that is not including places associated with mischievous supernatural beings such as Hobgoblins, Puck, Brownie and Boggarts, such as

Hob's Hurst House, in Monsal Dale in the Derbyshire Peak District. Many of these names are associated with the pre-historic megalithic culture from the Neolithic and Late Bronze Age period including chamber tombs, stone circles and standing stones, round barrows and linear ditches. For example, at the megalithic complex of Avebury in Wilthsire, the largest stone circle in Europe, we find several “Devil” associations;

the Devil's Branding Irons, Devil's Quoit, and

the Devil's Den.

As Leslie Grinsell points out in

Folklore of Prehistoric Sites in Britain many of these “Devil” place-names no doubt came about with the onset of Christianity; the gods of the old religion becoming the devil of the new. In many instances the association with the Devil may indicate that the monuments were constructed by a race unconnected or forgotten by the current inhabitants of the land. There can be little doubt that these “Devil” named monuments were seen as evil is witnessed by the destruction at Avebury which reached its peak during the 17th and 18th centuries, when many stones were broken up in burning pits or buried, before the antiquarians John Aubrey and William Stukeley took an interest in our megalithic heritage.

Sites with “Devil” names, or related traditions, occur mainly in England with fewer numbers in Scotland and Wales. Where “Devil” nomenclature and traditions are largely absent or rare, their place is often taken by figures from the Arthurian cycle. Oddly, after sites with “Devil” place names, Arthurian names and traditions are the most prevalent. As with the “Devil” place names, Arthurian traditions are commonly attached to megalithic sites dating from the Neolithic and Late Bronze Age period, including chamber tombs, stone circles and standing stones.

Stonehenge has been associated with Arthur since at least the time of Geoffrey of Monmouth, c.1136 AD, who called the monument the “

Giant's Dance”, according to Merlin after giants had transported the stones from Africa to Ireland. But giant folklore at other stone circles is relatively rare, however the stones at Callanish in the Western Isles of Scotland, are traditionally giants turned to stone for refusing to accept Christianity. If a similar tradition existed at the

Giant's Dance on Salisbury Plain it has been lost to us through time and although the stone circle is incomplete there is certainly no record of any destruction of Stonehenge as at Avebury.

After Stonehenge perhaps the most well known Arthurian sites are from the 9th century

Historia Brittonum, formerly attributed to a certain monk by the name of Nennius.

Dinas Emrys, the fortress of Ambrosius, near Beddgelert in Gwynedd, has been identified as the site of Vortigern's tower and the interned dragons in both the

Historia Brittonum and Geoffrey of Monmouth's version of

the tale of the prophetic fatherless boy.

Carn Cabal and

Wormelow Tump are listed amongst the Wonders of Britain (

Mirabilia) in early editions of the

Historia Brittonum.

Prolific in Wales is the name “

Arthur's Quoit”, (Coetan Arthur), typically megalithic burial chambers, found in Anglesey, Caernarvonshire, Merionethshire, and Carmarthenshire. Perhaps the most well known quoit is the famous cromlech

Pentre Ifan, once known as

Arthur's Quoit, in the Preseli Mountains, Pembrokeshire.

In West Glamorgan an ancient burial chamber named

Maen Ceti is also known as

Arthur's Stone.

Carn March Arthur is a rock overlooking the Dovey Estuary, on a hill above the A493, near

Llyn Barfog, the Bearded Lake, which bears a depression that is said to be the hoofprint of Arthur's horse.

Arthur's Table's (Bwrdd Arthur) are found on Anglesey as a hillfort and in Clwyd comprising a circle of holes cut into a hillside. Nearby is the ancient hillfort known as

Moel Arthur (Arthur's Hill). Further examples of Round Tables are found as an earthwork at Stirling Castle and Mayburgh in Cumbria. The capstone of some dolmens is often called

Arthur's Table.

The Stones of the Sons of Arthur (Cerrig Meibion Arthur) beneath Foel Cwmcerwyn, the highest point in the Preseli Hills, Pembrokeshire, commemorates four of Arthur's four champions, killed here in the pursuit of the supernatural giant boar, Twrch Trwyth, in the tale of

Culhwch and Olwen from the Mabinogion.

In Scotland there is

Arthur's Seat, Edinburgh and

Arthur's O'en, Stirlingshire, first mentioned in 1293 but nothing remains of it today.

The Eildon Hills lie to the south-east of Melrose, in southern Scotland. According to one legend, Arthur and his knights lie sleeping in a hidden cavern beneath the hills.

In England at Dorstone, east of Hay-on-Wye, a megalithic burial site of c.3000 BC is named

Arthur's Stone.

Terra Arturi

In 1113 AD a group of canons from Laon paid a visit to England. The event is described in a narrative,

De Miraculis Sanctae Mariae Laudensis (The Miracles of St Mary of Laon) by Henri from Laon, written in 1146 AD. From Exeter they journeyed through '

Danavexeria', probably meant to be ancient Dumnonia, roughly modern Devonshire, and here they were told they were entering the very land of the famous King Arthur, '

terra Arturi'. On their journey through Dartmoor they were shown various rock formations in open country such as

Arthur's Chair and

Arthur's Oven. These, with the

Mirabilia, are amongst the earliest documented Arthurian sites.

Further west on Bodmin Moor in Cornwall there is the flat rock outcrop known as

Arthur's Bed, and nearby the related

King Arthur's Troughs where he is said to have fed his hunting dogs. Nearby there are a pair of stone circles on

King Arthur's Downs, and

Arthur's Hunting Lodge, or

Hunting Seat, evidently this was his hunting ground. Further south on the moor is the enigmatic rectangular enclosure of 56 stones known as

King Arthur's Hall of uncertain date but first recorded in the 16th century. On the east side of Bodmin Moor is

Trethevy Quoit, another once known as

King Arthur's Quoit.

The Lair of the Grey Hound Bitch

Sites listed as quoits include chamber tombs known by their Welsh names for the kennel, or lair, of the grey hound bitch (

Cwt, Gwal, Llety or

Twlc-y-filiast),whose secondary name is typically

Arthur's Quoit. These sites are are said to be connected to the bitch Rhymhi and her two cubs included in the boar hunt from the Arthurian tale of

Culhwch and Olwen. More recent tradition has associated these sites with Ceridwen who chased the boy Gwion Bach while in the form of a grey hound in the

Tale of Taliesin.

|

| Pentre Ifan - Arthur's Quoit |

The word '

quoit' is usually applied to a discus, an object thrown for sport, but in megalithic terminology it usually refers to the capstone of prehistoric structures such as a cromlech or dolmen. The game of quoits is indeed ancient and probably originates from Ancient Greece, throwing a ring or disc, probably originally of stone, slightly convex on the outside, over a distance. It is easy to see how the capstone of a cromlech or dolmen would be seen to look like a giant's quoit. The word is thought to derive from Middle English '

coite' or '

coyte' first known in the 15th century, possibly from the French.

To this list we can add the megalithic sites associated with Merlin, such as

Merlin's Mound, Marlborough and

Merlin's Chair, Carmarthen. According to Geoffrey of Monmouth, Merlin is intimately linked with the building of Stonehenge and was born at Carmarthen, the city being named

Kaermerdin (Merlin's fortress) after him. An oak tree growing in the centre of the town was called

Merlin's Tree.

There are many more, this list is not exhaustive by any means and is not meant as a gazetteer but serves to demonstrate the many prehistoric sites associated with the Arthurian tradition. Although there is no record of Arthurian names for these prehistoric sites or landscape features and usage of words such as '

quoit' until the Late Middle Ages at the earliest we can be certain the process had begun centuries before Geoffrey of Monmouth's chronicle as attested by the

Historia Brittonum and supported by the later pre-Galfridian account of the canons from Laon.

Arthurian Geography

Arthurian geography in the search for a historical Arthur is at odds with these prehistoric landscape sites; here we seem to be dealing with another, often neglected, stratum of the Arthurian legend. The identification of the sites mentioned in Chapter 56 of the

Historia Brittonum, the so-called 'Arthurian Battle List', has evaded even the most avid historical battlefield detective.

Chester, Cheshire and

Caerleon, South Wales, both serve as contenders for the "

City of the Legion" the site of Arthur's ninth battle in the

Historia Brittonum, yet, as with the other battle sites, the rivers

Glein, Dubglas, Bassa and

Tribruit, the fort

Guinnion, the hill called

Agned, and so on, have defied positive identification. However, it is worth noting that prior to excavation, long after the Romans had been forgotten, the amphitheatre at Caerleon was covered by a grassy mound which was known locally as '

Arthur's Round Table'.

Further evidence of these conflicting traditions is found in the

The Stanzas of the Graves (Englynion y Beddau), found in the 13th-century Black Book of Carmarthen, but based on earlier material, where it is recorded that Arthur's grave is nowhere to be found. This of course concords with Geoffrey's account in the

Vita Merlini that states that Arthur, mortally wounded during his last battle, was taken to the Island of Apples, which is called the Fortunate Isle, to be healed by Morgen and her sisters.

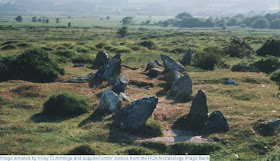

Whereas Geoffrey fails to provide a satisfactory end to Arthur's days, perhaps ancient tradition can offer an answer to Arthur's disappearance after his death. Overlooking the source of the Stonehenge Bluestones outcrop of Carn Meini in the Preseli Hills, Pembrokeshire, is an oval or horse-shoe shaped setting comprised of thirteen small standing stones. The site has never been excavated. It is known as

Bedd Arthur, 'The Grave of Arthur'.

© Edward Watson 2014

http://clasmerdin.blogspot.co.uk/

*

Further Reading:

Leslie V Grinsell,

Folklore of Prehistoric Sites in Britain, David & Charles, 1976.

Geoffrey Ashe,

Arthurian Britain: The Traveller's Guide, Gothic Image, 2002.

F J Snell,

King Arthur's Country, Dutton & Co, 1926

Michael D. Reeve (editor) and Neil Wright (translator),

The History of the Kings of Britain: An edition and translation of the De gestis Britonum (Historia Regum Brittannie) by Geoffrey of Monmouth, Boydell Press, 2009.

Neil Fairbairn,

A Traveller's Guide to the Kingdoms of Arthur, Evans Brothers, 1983.

* * *