[Grail]...….(in medieval legend) the cup or platter used by Christ at the Last Supper, and in which Joseph of Arimathea received Christ's blood at the Cross. Quests for it undertaken by medieval knights are described in versions of the Arthurian legends written from the early 13th century onward.

The Story of the Grail

Today we see the Holy Grail as a legendary sacred vessel used by Christ at the Last Supper, identified with the chalice of the Eucharist. Three of the four Gospels of the New Testament specifically mention a cup or platter at the Last Supper when Christ poured wine into a cup and urged the Disciples to drink of his blood.

This same vessel is said to have been the dish used by Joseph of Arimathea to gather the Precious Blood of Christ at the deposition. But none of the Gospels mention a vessel used by Joseph of Arimathea, or anyone else, to collect the Blood of Christ while on the Cross.

|

| The Last Supper |

The story of the Grail commences with Chrétien de Troyes and was entitled Perceval, le Conte du Graal (Perceval, or the Story of the Grail), written between 1180 and 1190 AD. No extant manuscript containing Chrétien’s romances is contemporary with the author himself. Chrétien fails to describe the Grail in any great detail, and refers to it as simply “a grail” (un graal) as if his readers would be familiar with this term. An alternative argument suggests Chrétien did not himself understand what the 'Grail' actually was. Chrétien writes of the Grail in only 25 of some 9,000 lines of the Conte du Graal. However, the grail was not the main subject of Chrétien's work; he wrote about Perceval's adventures and then Gawain who took up the quest.

In Chrétien's tale, Perceval witnesses a procession when he stays the night at the Fisher King's castle. Leading the procession is a squire carrying a white lance that drips blood from its tip. The procession continues with candelabras and then a maiden brings a "grail” that is so radiant it appears to dim the light from the candles. Perceval fails to ask what the lance or the grail are. The next morning the castle appears deserted and he leaves.

After wondering for five full years Perceval eventually meets a hermit, who is also his uncle, and is rebuked for bearing arms on Good Friday. The hermit explains that the Grail is a “holy thing” which sustains the Fisher King's father, the Grail King, by serving a single mass wafer. The passage bears extensive reference to the Passion and holds deep Christian feeling but oddly contains an exceptionally bitter mention of the Jews “who should be killed like dogs”. This passage has been described as untypical of Chrétien who normally writes in an unemotional and tolerant manner. Consequently the passage has been identified as an addition to the original manuscript by a later hand.

Chrétien's story then switches to Gawain who goes in search of the bleeding lance for one year. A vassal foretells that the lance will one day destroy the kingdom of Logres (England). Unfortunately Chrétien's account breaks off virtually mid-sentence and was left incomplete. This has led to a multitude of tales following Chrétien that have attempted to fill in the gaps with divergent interpretations and, notably, the description of the Grail.

A series of Continuations and Prologues (The Elucidation) of the Conte du Graal, composed c.1200-1230, added another 40,000 lines in an attempt to bring Chrétien's tale to a satisfactory conclusion with Gawain finally attaining the Holy Grail, but in reality confused the matter even further mixing pagan Celtic themes with further Christianisation of the Grail. In the First Continuation the bleeding lance is identified as the spear used by Longinus to pierce Christ's side when he hung on the cross. There had been much interest in the lance since it was discovered in Antioch in 1098 during the First Crusade.

Inspired by the equation of Chrétien's lance with that of the crucifixion, the addition of the Grail as a second relic of the Passion soon followed. A passage identified as a clear interpolation into some manuscript copies of the First Continuation tells how the Grail was the vessel in which Christ's blood was caught by Joseph of Arimathea who subsequently brought it to England where it has been ever since in the safe keeping of one of his descendants. The interpolator seems to hold a preoccupation with the circumstances of the Passion and the part played by the Jews; the passage in the First Continuation bears a strong resemblance to the hermit passage in the Conte du Graal and we can justifiably suspect the same hand as being responsible. But it remains unanswered as to what inspired the interpolator of Conte du Graal to Christianise the objects of Chrétien's grail procession into relics of Christ's Crucifixion?

Thus, the Christian mysticism of the Grail begins with with the First Continuator - not Chrétien, who's original work never links the grail with the chalice of the Last Supper; it is probable that he had something else in mind. We have no record of Chrétien's death; perhaps he purposefully left his work unfinished as a master stroke to puzzle us still 800 years later? If so it certainly worked. But it also left the Grail open to the interpretations of a multitude of other writers.

.jpg) |

| The Damsel of the Holy Grail Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1874) |

According to Wolfram, Kyot had uncovered a forgotten Arabic manuscript written by Flegetanis, a Muslim astronomer who had found the secrets of the Grail written in the stars. However, many sceptics believe Kyot the Provençal was simply a literary device invented by Wolfram to permit his deviations from the Conte du Graal, but as with Chrétien, Wolfram does not link the Grail with the Chalice of the Last Supper. Significantly the first two medieval romances to feature the Grail do not link it with a relic of the Passion.

Robert de Boron was the first author to give the Holy Grail myth an explicitly Christian dimension when it became the 'Holy Grail' the vessel used by Christ at the Last Supper. Boron was author of two surviving poems, the Joseph d'Arimathe and the Merlin, thought to have been part of an intended trilogy along with the Perceval which has not survived.

Relics of the Passion

In de Boron's account the emphasis was placed firmly on the history of the Grail as a Holy relic, whereas Chrétien's focus was firmly on the adventures of Perceval and then Gawain. Chrétien's simple serving dish, “un graal,” had now developed into the Holy Grail, a Christian relic of the Passion brought back from the Holy Land. Clearly, de Boron had something quite different in mind to Chrétien and Wolfram.

According to Boron, writing between 1200 to 1210 AD, relying heavily on apocryphal texts omitted from the official version of the Bible such as the Gospel of Nicodemus, Joseph of Arimathea used the Grail to catch the last drops of blood from Christ's body as he hung on the cross. Joseph's family brought the Grail to the vaus d'Avaron, in the west, which later poets identified with Avalon at Glastonbury. These ideas seem to have been inspired by the patrons of the Grail Romances on returning from the Holy Land.

At the end of the Joseph d'Arimathe de Boron states he is in the service of Gautier of "Mont Belyal", identified as Gautier de Montbéliard who departed on the Fourth Crusade in 1202 AD and died in the Holy Land. Robert is said to have been originally from the village of Boron in the district of Montbéliard.

Philip of Alsace, count of Flanders from 1168 to 1191 AD, was the man said to be the patron of Chrétien's last romance, Conte du Graal. In the opening lines, Chrétien honours Philip with praise for providing him with the book he adapted into the "best tale ever told in a royal court". Philip's father was Thierry of Alsace, also known as Diederik van den Elzas, Count of Flanders from 1128 to 1168 AD, who joined the Second Crusade in 1147 AD.

According to tradition, Thierry returned to his capital Bruges on 7th April, 1150 AD, with the relic of the “Precious Blood” a cloth that Joseph of Arimathea used to wipe blood from the body of Christ after the Crucifixion. The Basilica of the Holy Blood was built between 1134 and 1157 AD as the chapel of the residence of the Count of Flanders, to house the venerated relic of the Holy Blood. However, this cannot be verified until 1256 AD and we cannot dismiss the possibility that it was a later invention.

However, as we have seen above, the writers of the Continuations, clearly felt that Chrétien's tale was meant to conclude with the relics of the Passion.

The Early History of the Grail

The earliest accounts of the Grail appear to have formed their roots from contact with the Holy Land during the Crusades. Many claimants to the Holy Grail are cited as relics brought back from the Holy Land during this period; perhaps we should not be surprised as the recovery of Christian relics was the stimulus for the Crusades; Pope Urban II delivered his “call to arms” speech at the Council of Clermont on 27 November 1095 to liberate the eastern churches.

Before Robert de Boron and the Continuations of Chrétien's Conte du Graal produced these literary renditions of the Holy Grail there were stories of relics from the Passion. Relics claiming to be the Holy Lance, Holy Sponge, Holy Chalice, the Crown of Thorns and nails from the cross were all venerated well before 1,000 AD.

Writing around 1200 AD, the first reference outside of the Bible to the dish of the Last Supper, the Cistercian chronicler Helinandus recorded that in 717 AD a hermit was shown a vision of the dish of the Last Supper. This learned hermit then wrote a book in Latin, entitled Gradale, the medieval Latin for ‘dish’; in English it was the 'Grail'.

But the earliest account of the Chalice and Lance to be recorded appears in the account of Arculf, a pilgrim who travelled from the British Isles to Palestine in the 7th century, and claimed he saw both the Chalice of the Last Supper and the Holy Lance that pierced the side of Christ when he hung on the cross.

On his return from a pilgrimage to the Holy Land (c. 680), Arculf was driven by storm to Scotland and so arrived at the Hebridean island of Iona, where he related his experiences to his host, Abbot St. Adamnan. Adamnan’s narrative of Arculf’s journey, De locis sanctis (Concerning Sacred Places), was noted by Bede, who inserted a brief summary of it in his Ecclesiastical History of the English People.

Arculf claimed he touched and kissed the silver chalice, which had the measure of a Gaulish pint and two handles on either side, through an opening of the perforated lid of the reliquary in a chapel between the basilica of Golgotha and the Martyrium, near Jerusalem. He saw the Holy Lance in the porch of the basilica of Constantine. This is the earliest mention of the Chalice of the Last Supper in the Holy Land and the only account that claims it is made of silver. Nothing is heard of it again.

Ecclesia

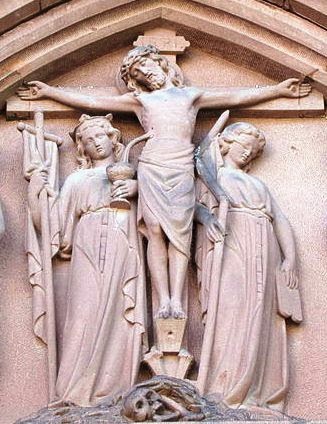

Perhaps the earliest depiction of the "Holy Grail" is found in the 9th century in a psalter showing a figure at the Crucifixion collecting Christ's blood in a chalice. A miniature from the mid-9th century Utrecht Psalter shows an unidentified figure with a halo at the foot of the cross with a chalice into which Christ's blood flows. This figure is usually described as Ecclesia.

Ecclesia appears with a female Jewish partner (Church and Synagogue) in several pieces of later Carolingian art featuring the Crucifixion dating from c.870 AD and commonly appearing in miniatures and various small works until the 10th century. Ecclesia first appears in a Crucifixion scene in the Drogo Sacramentary of c.830 AD.

|

| Crucifixion with Ecclesia and Synagoga, Notre-Dame des Douleurs, Marienthal, Alsace |

Significantly, illuminated Gospel manuscripts always depict the figures at the side of the Crucifixion as Ecclesia and Synagoga, with Ecclesia always collecting the blood of Christ in a chalice. Whereas de Boron's Joseph of Arimathea and Nicodemus only appear in Crucifixion scenes in Medieval Grail manuscripts with one exception. An illuminated manuscript at Weingarten Abbey in Germany is illustrated with a Crucifixion scene showing what appears to be Joseph and Nicodemus removing Christ's body from the cross and an unidentified figure holding a chalice collecting the Holy blood. This manuscript pre-dates Robert de Boron's history of the Grail by a hundred years, suggesting the story was in circulation well before de Boron penned his account. Significantly, Wiengarten houses the Holy relic of the Precious Blood said to have been caught in a leaden box from the wound inflicted in Christ's side by Longinus.The box was buried at Mantua in Lombardy, Italy, and miraculously discovered in 804 AD.

In Christiain iconography the personification of Ecclesia preceded her coupling with Synagoga by several centuries, where she is depicted as the Bride of Christ, the church was in this context conflated with the Virgin, leading to the concept of Maria Ecclesia, or Mary as the church.

Is the depiction of Ecclesia bearing the chalice containing Christ's blood the origin of the Grail Maiden? There is evidence, pre-dating the first Grail Romance of Chrétien, suggesting that this is indeed the case.

Copyright © 2014 Edward Watson

http://clasmerdin.blogspot.co.uk

Notes & References

DDR Owen, The Evolution of the Grail Legend, University of St Andrews, 1968.

Richard Barber, The Holy Grail: Imagination and Belief, Allen Lane, 2004.

* * *

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.