- Simon Keegan, Pennine Dragon, New Haven Publishing,14 March 2016,

- Graham Phillips, The Lost Tomb of King Arthur, Bear & Company, 19 May 2016,

- Chris Barber, King Arthur: The Mystery Unravelled, Pen & Sword History, 30 June 2016.

The Real King Arthur of the North

Pennine Dragon: The Real King Arthur of the North by Simon Keegan (New Haven Publishing,14 March 2016) claims to be the definitive work on the true King Arthur published in the 1500th anniversary of Arthur's greatest victory at Badon.1

A journalist from the Daily Mirror newspaper's Manchester office, author Simon Keegan expected to find Arthur in the south-west of England as the legend claims but after years researching the ancient texts he says it is possible to prove that Arthur was from the Lancashire-Yorkshire area.

The popular image of King Arthur is a medieval knights in shining armour possessing a magic sword and advised by a wizard could not be further from the reality of the historic Arthur was first recorded much earlier as a warleader fighting invading Saxons in the 6th century. Keegan therefore chose the statue of Constantine at York, apparently an ancestor of Arthur, for the cover of his book because he wanted to show what a true Romanised leader like Arthur would look like rather than a latter day medieval knight.

Keegan argues that Arthur was always identified as a man of the north in the earliest historical references and identifies Arthur's battles as being fought across the north of England and lowlands of Scotland.

Pennine Dragon claims the historic Arthur was a Yorkshireman, identified as Arthwys ap Mar, King of Ebrauc and the Pennines, whose father was King in the York area and whose kingdom stretched from Hadrian’s Wall down to Yorkshire and Lancashire with Camelot identified as the Roman fort at Slack, Outlane near Huddersfield situated alongside the Roman road, although today under the carpark of the local golf club, adjacent the M62. Keegan claims we find that Arthwys was at precisely the right time and place and is the only possible man who could have been the King Arthur of legend.

The Antonine Itinerary records a place named 'Camboduno' somewhere in the West Riding of Yorkshire on Iter II (the second major road in Britain) situated between Calcaria (Tadcaster, North Yorkshire) and Mamucio (Manchester). This appears to be the same station named as 'Camulodunum' (Camulod) listed in the 7th century Ravenna Cosmology, the name possibly transferred from the native hillfort of Almondbury, some five miles away, after the ancient Celtic War-God, Camulos.

Initial excavations revealed the Roman fort was established in the 1st century and abandoned in the 2nd century, yet further work by Huddersfield and District Archaeological Society has shown there was activity on the site for at least another 200 years, into the Arthurian period. Keegan sees this fort as a strong contender for the original Camelot.

Other locations identified with the Arthurian legend such as Badon, Camlann, Avalon and the Round Table are all, predictably, identified in the north. Keegan also claims to have identified fifty Arthurian characters as real historical figures from the area. He identifies Lancelot and Galahad as LLaenauc and Gwallawg respectively, kings of the ancient British kingdom of Elmet.

In Pennine Dragon Arthur's wife, the Guinevere of legend (Welsh: Gwenhwyfar), is identified as St Cywair (born 455 AD), an Irish Saint known as the Queen of the Pennines. And just as the legendary Guinevere ended her days in a monastery, Cywair (Welsh: Gwyr) apparently finished her days in the church now called St Cywair's in Llangower, at the south end of Bala Lake (Llyn Tegid) in Wales. The ancient church at Llangower is dedicated to her memory with her feast day still celebrated there on 11th July. Nearby is a holy well named Ffynnon Gower claimed to possess healing properties, the water regarded as a cure for all ailments. There is a late 17th century reference to an associated standing stone, Llech Gower.

In Welsh tradition Gwyr was a 5th century Irish princess who married the king of the North Britons and the mother to St Pabo and Llywarch Hen, the early Welsh bard. According to local tradition there was another well in this area but the well keeper forgot to put the cover over it which caused the flood which formed Llyn Tegid.

Pennine Dragon’s 'Camelot' Protected Status

Since the publication of Pennine Dragon in March 2016 the Roman fort at Slack, situated on a strategic location on the Roman road from Chester to York, named 'Camulod' or 'Cambodunum' which Keegan identifies with Arthur's Camelot, has received further protected status from Historic England (formerly English Heritage) who has extended the schedule to include the area of the Romano-British vicus.

At Slack, as with many other military sites of the Roman period, the vicus, the area of civilian settlement, has received little attention and the potential for continuation of civilian activity on the site not fully examined.

Work on the vicus at Slack by the Huddersfield and District Archaeological Society during three seasons of excavation in 2007, 2008 and 2010 made very significant discoveries which has produced evidence for the period of Roman occupation from about 80 AD to 340 AD, extending it well into the 3rd and possibly 4th centuries leading to reconsideration of the later use of the site.

Radiocarbon dating and pottery analysis from the vicus area adjacent to the fort has provided evidence of considerable late activity indicating that the settlement lasted for perhaps 200 years after the fort was demilitarised.2

Arthur of the Pennines

In the genealogical tract 'The Descent of the Men of the North' (Bonedd Gwŷr y Gogledd), extant in several manuscripts, notably the 13th century manuscript Peniarth MS45, can be found the pedigrees of twenty 6th-century rulers of the 'Old North' (Hen Ogledd). This text records the great grandson of Coel Hen (Old King Cole c.385-415) as Arthwys ap Mar who lived from about 460-520, mirroring the flourit of Arthur of Badon.

Arthwys ap Mar does not appear in all the genealogies, indeed to some extent he is as shadowy a figure as Arthur. When he is listed it is always as son of Mar, grandson of Ceneu, great grandson of Coel. However, these pedigrees show evidence of manipulation by Welsh genealogists to provide links to the British Heroes of the Old North. Thus, the name 'Ceneu' appears as a phantom entry arising from a misunderstanding of a reference to 'ceneu' in the poem Gweith Argoed Llwyfein by Talisien. Sir Ifor Williams has argued that the word 'vab' (son of) had been erroneously added by a Welsh scribe who assumed Ceneu vab Coel to be a personal name. Subsequently, Ceneu as a descendant of Coel was accepted by copyists and scholars alike, when according to Williams it should read as “And a whelp of Coel would be a hard-pressed warrior before he would hand over any hostages.”3

However, similarity of name and time falls a long way short in providing proof that Arthur of the Pennines is THE King Arthur of Badon. But it does raise the interesting possibility as to whether some deeds ascribed to Arthwys in long-lost ancient northern texts were known by Nennius and Geoffrey of Monmouth who later ascribed these feats to Arthur in their respective works.

In his Historia Regum Britanniae (c.1136) Geoffrey writes of a pre-Arthurian king named Archgallo who wanders hopelessly, deposed and dejected, with just ten knights through the Forest of Calaterium. Geoffrey places the Forest of Calaterium in Albany (Scotland), the place he has Brennius battle with Belinus, located remarkably close to the Forest of Caledon (Celidon) the site of another Arthurian battle.

Alternatively, it has been suggested that Calaterium may have been the Forest of Galtres (Thompson and Giles), an ancient Royal Forest north of York which extended up to the City walls, now long obliterated owing to deforestation in the 17th century, placing Archgallo directly in the territory of Arthwys ap Mar. Archgallo is almost certainly based upon Arthur of the Pennines; Geoffrey even has him crowned at York. Geoffrey seems to have taken Archgallo's family, such as Elidurus and Peredurus from the line of Arthwys featuring his son Eliffer Gosgorddfawr (of the Great Host) and his twin sons, Gwrgi and Peredyr who are remembered for their victory over King Gwenddoleu at the Battle of Arfderydd (Arthuret in Cumbria).

Geoffrey seems to be recalling a long-remembered story of the North which may have contained an element of truth in the record of the battles of Arthwys. It has long been suspected that Geoffrey had access to a now lost Northern Chronicle which recorded the deeds of Arthwys, some of which he seems to have confused with Arthur of Badon. For example, Geoffrey locates Arthur's battle on the river Douglas just outside of York.

In truth the Arthurian battle sites listed in Nennius (Historia Brittonum, Section 56, c.829) are unidentifiable and can be made to fit almost any location; they can certainly be made to suit a northern identification and therefore used in an argument for an Arthur of the North who battled against the Saxons.

The story of Arthwys of the Pennines may certainly be homogeneous with that of Arthur to a degree, and this may be as close as we will get to the discovery of a historic King Arthur; indeed Geoffrey of Monmouth seems to have conflated the two characters in writing of the northern deeds of Arthur.

Yet Arthur is never referred to as 'Arthwys' in vernacular sources and although the Welsh personal name Arthwys is well documented it is an entirely separate name from 'Arthur'. Indeed, the Welsh form of Arthur is exactly that: Arthur – not Arthwys.4

>> The Real King Arthur Thrice Discovered Book II: The Lost Tomb

Notes

1. It is arguable if Arthur, the Dux Bellorum, actually fought at Badon, but to distinguish that character from the subject of Keegan's book he is referred to here as Arthur of Badon.

2. The Romans in Huddersfield - A New Assessment, British Archaeological Reports Vol 620, 2015.

3. Tim Clarkson, The Men of the North, 2010.

4. Caitlin (Thomas) Green, The Historicity and Historicisation of Arthur.

|

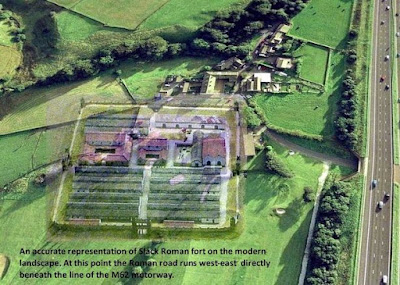

| The Roman fort at Slack, Outlane, as it may have looked 2,000 years ago superimposed on the landscape now, in context with the M62 |

Initial excavations revealed the Roman fort was established in the 1st century and abandoned in the 2nd century, yet further work by Huddersfield and District Archaeological Society has shown there was activity on the site for at least another 200 years, into the Arthurian period. Keegan sees this fort as a strong contender for the original Camelot.

Other locations identified with the Arthurian legend such as Badon, Camlann, Avalon and the Round Table are all, predictably, identified in the north. Keegan also claims to have identified fifty Arthurian characters as real historical figures from the area. He identifies Lancelot and Galahad as LLaenauc and Gwallawg respectively, kings of the ancient British kingdom of Elmet.

In Pennine Dragon Arthur's wife, the Guinevere of legend (Welsh: Gwenhwyfar), is identified as St Cywair (born 455 AD), an Irish Saint known as the Queen of the Pennines. And just as the legendary Guinevere ended her days in a monastery, Cywair (Welsh: Gwyr) apparently finished her days in the church now called St Cywair's in Llangower, at the south end of Bala Lake (Llyn Tegid) in Wales. The ancient church at Llangower is dedicated to her memory with her feast day still celebrated there on 11th July. Nearby is a holy well named Ffynnon Gower claimed to possess healing properties, the water regarded as a cure for all ailments. There is a late 17th century reference to an associated standing stone, Llech Gower.

In Welsh tradition Gwyr was a 5th century Irish princess who married the king of the North Britons and the mother to St Pabo and Llywarch Hen, the early Welsh bard. According to local tradition there was another well in this area but the well keeper forgot to put the cover over it which caused the flood which formed Llyn Tegid.

Pennine Dragon’s 'Camelot' Protected Status

Since the publication of Pennine Dragon in March 2016 the Roman fort at Slack, situated on a strategic location on the Roman road from Chester to York, named 'Camulod' or 'Cambodunum' which Keegan identifies with Arthur's Camelot, has received further protected status from Historic England (formerly English Heritage) who has extended the schedule to include the area of the Romano-British vicus.

At Slack, as with many other military sites of the Roman period, the vicus, the area of civilian settlement, has received little attention and the potential for continuation of civilian activity on the site not fully examined.

Work on the vicus at Slack by the Huddersfield and District Archaeological Society during three seasons of excavation in 2007, 2008 and 2010 made very significant discoveries which has produced evidence for the period of Roman occupation from about 80 AD to 340 AD, extending it well into the 3rd and possibly 4th centuries leading to reconsideration of the later use of the site.

Radiocarbon dating and pottery analysis from the vicus area adjacent to the fort has provided evidence of considerable late activity indicating that the settlement lasted for perhaps 200 years after the fort was demilitarised.2

Arthur of the Pennines

In the genealogical tract 'The Descent of the Men of the North' (Bonedd Gwŷr y Gogledd), extant in several manuscripts, notably the 13th century manuscript Peniarth MS45, can be found the pedigrees of twenty 6th-century rulers of the 'Old North' (Hen Ogledd). This text records the great grandson of Coel Hen (Old King Cole c.385-415) as Arthwys ap Mar who lived from about 460-520, mirroring the flourit of Arthur of Badon.

Arthwys ap Mar does not appear in all the genealogies, indeed to some extent he is as shadowy a figure as Arthur. When he is listed it is always as son of Mar, grandson of Ceneu, great grandson of Coel. However, these pedigrees show evidence of manipulation by Welsh genealogists to provide links to the British Heroes of the Old North. Thus, the name 'Ceneu' appears as a phantom entry arising from a misunderstanding of a reference to 'ceneu' in the poem Gweith Argoed Llwyfein by Talisien. Sir Ifor Williams has argued that the word 'vab' (son of) had been erroneously added by a Welsh scribe who assumed Ceneu vab Coel to be a personal name. Subsequently, Ceneu as a descendant of Coel was accepted by copyists and scholars alike, when according to Williams it should read as “And a whelp of Coel would be a hard-pressed warrior before he would hand over any hostages.”3

However, similarity of name and time falls a long way short in providing proof that Arthur of the Pennines is THE King Arthur of Badon. But it does raise the interesting possibility as to whether some deeds ascribed to Arthwys in long-lost ancient northern texts were known by Nennius and Geoffrey of Monmouth who later ascribed these feats to Arthur in their respective works.

In his Historia Regum Britanniae (c.1136) Geoffrey writes of a pre-Arthurian king named Archgallo who wanders hopelessly, deposed and dejected, with just ten knights through the Forest of Calaterium. Geoffrey places the Forest of Calaterium in Albany (Scotland), the place he has Brennius battle with Belinus, located remarkably close to the Forest of Caledon (Celidon) the site of another Arthurian battle.

Alternatively, it has been suggested that Calaterium may have been the Forest of Galtres (Thompson and Giles), an ancient Royal Forest north of York which extended up to the City walls, now long obliterated owing to deforestation in the 17th century, placing Archgallo directly in the territory of Arthwys ap Mar. Archgallo is almost certainly based upon Arthur of the Pennines; Geoffrey even has him crowned at York. Geoffrey seems to have taken Archgallo's family, such as Elidurus and Peredurus from the line of Arthwys featuring his son Eliffer Gosgorddfawr (of the Great Host) and his twin sons, Gwrgi and Peredyr who are remembered for their victory over King Gwenddoleu at the Battle of Arfderydd (Arthuret in Cumbria).

Geoffrey seems to be recalling a long-remembered story of the North which may have contained an element of truth in the record of the battles of Arthwys. It has long been suspected that Geoffrey had access to a now lost Northern Chronicle which recorded the deeds of Arthwys, some of which he seems to have confused with Arthur of Badon. For example, Geoffrey locates Arthur's battle on the river Douglas just outside of York.

In truth the Arthurian battle sites listed in Nennius (Historia Brittonum, Section 56, c.829) are unidentifiable and can be made to fit almost any location; they can certainly be made to suit a northern identification and therefore used in an argument for an Arthur of the North who battled against the Saxons.

The story of Arthwys of the Pennines may certainly be homogeneous with that of Arthur to a degree, and this may be as close as we will get to the discovery of a historic King Arthur; indeed Geoffrey of Monmouth seems to have conflated the two characters in writing of the northern deeds of Arthur.

Yet Arthur is never referred to as 'Arthwys' in vernacular sources and although the Welsh personal name Arthwys is well documented it is an entirely separate name from 'Arthur'. Indeed, the Welsh form of Arthur is exactly that: Arthur – not Arthwys.4

>> The Real King Arthur Thrice Discovered Book II: The Lost Tomb

Notes

1. It is arguable if Arthur, the Dux Bellorum, actually fought at Badon, but to distinguish that character from the subject of Keegan's book he is referred to here as Arthur of Badon.

2. The Romans in Huddersfield - A New Assessment, British Archaeological Reports Vol 620, 2015.

3. Tim Clarkson, The Men of the North, 2010.

4. Caitlin (Thomas) Green, The Historicity and Historicisation of Arthur.

* * *

Thanks for the write-up. Very nicely written. Best wishes, Simon Keegan.

ReplyDeleteThanks Simon, good luck with the book.

DeleteAny plans for a follow up?

Ed

Yes, we have a hardback edition out in a few weeks and I've already started work on the follow up. I'll let you know as soon as it starts to take shape.

DeleteIt is welcomed that the publicity this book has created has led to an increase in the level of protection awarded to the site of the vicus at Slack Roman fort, the latest dating evidence gleaned from excavations under Hobson extends activity to the fourth-century. By any account a historical King Arthur would have ruled in the late-fifth century to early sixth-century, died Camlann c.520. There is absolutely nothing to link Slack with King Arthur.

ReplyDeleteAnd if you think that was bad what till you read the sequel, 'The Lost Book of King Arthur' - apparently The Rudge Cup is the 'Grail'.

ReplyDeleteHi Frank, I didn't know the follow up book had been published, Simon did say in his comment above that he would let us know when it started to take shape, but he's not been in touch. Perhaps he didn't like my post on Pennine Dragon.

DeleteHowever, I've not heard of the Rudge Cup being called the Grail before and never considered an Arthurian association.