The Petuaria ReVisited Project, currently investigating the Roman site at Brough on Humber in the East Riding of Yorkshire, has been making the news recently: ‘Dig sheds light on Roman history of town’, (BBC News, 3 August 2024)

.jpg) |

This Roman site, located about 12 miles west of Hull on the north bank of the Humber, has a rather unclear history with its full size and status yet to be determined.

It is generally agreed that the settlement at Brough on Humber started life as a Roman fort, Petuaria, around 70 AD, then abandoned by 125 AD. The historian and archaeologist Sheppard Frere claims earthwork defences were added during the Hadrianic period (117 AD to 138) for a short re-occupation which he suggests could be connected with the time when Hadrian became emperor as his biographer writes "the Britons could no longer be held under Roman control" which Frere interprets as indicating there was war in Britain.1

Frere suggests the early fort may have been a 30-acre site for a legionary vexillation or group of auxiliary regiments organised as a battle group, as at Derventio, modern Malton.2

By the middle of the 2nd century military occupation of the site had ceased and a civilian town was arising over the site of the Roman fort. Frere suggests that the Roman site at Brough, strategically placed on the north bank of the Humber estuary, may have remained in use as an army supply depot.3

The civil settlement expanded across the site of the fort replacing it with a walled settlement surrounded by a turf and timber rampart. The site was refortified during the later 3rd and early 4th century with a stone wall. Archaeologists believed that many of the original Roman buildings had been destroyed as the town developed over the years. The site certainly has a complex history which has led to confusing interpretations.

The Roman walls at Brough have been known about since the 1930s, but recent archaeological excavations by The Petuaria ReVisited Project have led to new discoveries with ground penetrating radar (GPR) revealing the remains of ditches, roads and walls and located what it is believed to be a Roman road in a nearby garden.

Petuaria marked the southern end of the Roman road known now as Cade's Road, which ran roughly northwards for a hundred miles to Pons Aelius (modern Newcastle upon Tyne). The section from Petuaria to Eboracum (York) was also the final section of Ermine Street.

|

| The Roman Roads of Britain (Roman Roads Research Association) |

In 1936 a stone-lined burial was found on the western side of the Roman road to York, as with the usual Roman custom interred outside the town walls. The grave contained an iron-bound wooden bucket and two sceptres, which has led to identification of the inhumation as a priest. The two sceptres had been intentionally bent and broken in preparation for their owner’s new life in the Otherworld. The intentional destructive treatment of grave goods is a native burial rite, found at many other sites across Britain, much has been found in the river Thames for example. Frere adds that nothing could illustrate better the dual character of the Romano-British civilisation; outwardly Roman, yet inwardly it remained Celtic.4

The Petuaria ReVisited Project team, including more than a hundred volunteers, are also re-visiting the Roman defences at Burrs playing field in the centre of the modern town. Recent geophysical surveys and excavations have shown many structures lie under the field.

During the 1930s archaeological excavations were carried out at Burrs Playing Field (formerly known as Bozzes Field), which revealed traces of a stone wall, buildings and a sequence of fortified structures. However, the highlight of these excavations was the discovery of a stone inscription found lying on its edge 30m south-west of the east gate of the Roman town in 1937. Catalogued as RIB 707, the inscription refers to the dedication of a theatre and has been interpreted as referring to the capital, or the civitas, of the Parisi. The identification of Petuaria with Brough-on-Humber has depended almost entirely on this inscription.

Ptolemy, who probably never visited Britain, became confused with the location of his so-called polis of the Parisi. Rivet and Smith note that Ptolemy correctly records a distance from London to Petuaria of 170 miles, but the ancient geographer logs the distance from Eboracum (York) to Petuaria as 45 miles, when the true distance is 30 miles.5 Ptolemy’s distance would put his polis somewhere on the east coast of Yorkshire.

One would expect the location of Petuaria to be clear in the Roman Road network, as the roads go there, yet with regard to The Antonine Itinerary: ITER I, Rivet and Smith write that after York serious problems arise.

ITER I runs from the Roman fort at Bremenium (High Rochester), north of Hadrian’s Wall, to Praetorio, somewhere in east Yorkshire. Following Dere Street the route runs along the eastern side of the Pennines to York. As Rivet & Smith note, the route south of York is not clear and has been the subject of much debate over the years. After York (Eboracum) the route is recorded as travelling to three forts Derventione, Delgovicia then Praetorio. For many years Derventio has been identified as the fort at Malton, on the river Derwent, which the Notitia Dignitatum records as garrisoned by the Numerus Supervenientum Petueriensium.6

The British archaeologist and specialist in the translation of Latin text and epigraphy Roger Tomlin proposes that Numerus Supervenientum Petueriensium was a military unit, where Petueriensium would appear to refer to the fort of Petuaria, whose soldiers could have been reinforcing the fort at Malton.7 It follows that owing to the proximity of Petuaria to Malton the assumption has manifested that Derventio must be Malton.

However, the counter-argument is that Derventio is not Malton, but the Roman site south west of Stamford Bridge, also on the Derwent. It follows that if Derventio is Stamford Bridge, then Malton must be Delgovicia.8

The lies confusion with Praetorio that has been identified as Petuaria (Brough on Humber) because of the similarity of the names. Rivet & Smith argue that Praetorio is not actually a proper name, rather it is a descriptive term meaning an official residence. They also suggest Delgovicia could be a site near Wetwang and conclude that Praetorio should be accepted as a corruption of the name Petuaria since the roads lead there.9

However the distances don’t work; the Itinery records 26 miles from Praetorio to Delgovicia (Malton), then a further 13 miles from Delgovicia to Derventio (Stamford Bridge), a total of 39 Roman miles. Whereas Petuaria is 26 Roman miles from Stamford Bridge, and 33 from Malton. As a solution Praetorio has been identified as Bridlington on the east Yorkshire coast.10

And just to confuse matters further, Petuaria appears in the Ravenna Cosmography as Decuaria which according to Rivet and Smith is best explained as a simple miscopying.11

The Inscription

The inscription has been translated as:

RIB 707: "For the honour of the divine house of the Emperor Caesar Titus Aelius Hadrianus Antoninus Augustus Pius, father of his country, consul for the second time, and to the Divinities of the Emperors, Marcus Ulpius Januarius, aedile of the vici of Petuaria, presented this [new] stage at his own expense." 12

|

| RIB 707 (Roman Inscriptions of Britain) |

From this we can see the town possessed a theatre whose new stage was presented by a Roman named M Ulpius Ianuarius, aedile of the vicus of Petuaria, who set up the tablet in honour of Antoninus Pius (emperor from AD 138 to 161).13

The Theatre

The theatre is important because it links the site to the inscription and would confirm its place in history. Yet, as much as archaeological investigations have searched it has remained elusive for many years. Frere states that this theatre is known only from the inscription (RIB 707) and the physical remains are yet to be discovered.14 Needless to say, its discovery would be a major find for The Petuaria ReVisited Project.

In 2018 specialist ground scanning equipment revealed the remains of buildings with rooms arranged around a courtyard, interpreted as a forum and a substantial D-shaped feature under the playing field; was this the long lost theatre referred to in the inscription?

In 2020 a trench was cut over the D-shaped feature. At the northern end of the trench, the team uncovered a hearth that contained a burnt coin dating to around AD 330. Following two seasons of excavations over the D-shaped feature the team has failed to find the theatre. With the absence of the theatre one must question if the inscription originated at this site or was brought in from another location?

However, they have found evidence of continued Roman activity in Brough into the late 4th and probably 5th centuries AD, longer than previously thought, contra Wacher (see below), who suggested that it had faded out of use by the early 4th century.

Civitas?

The reign of Antoninus Pius saw great advances in the towns of Britain; at Brough a small town was developing on the site of the recently evacuated Roman fort at Petuaria, and a theatre was built during his reign.

Theatres were relatively rare in Roman Britain, only three others are definitely known, from the major settlements at Verulamium (St Albans), civitas capital for the Catuvellauni, Durovernum, (Canterbury), civitas capital of the Cantiaci and Camulodunum (Colchester), the first Roman capital of the province. A ceramic theatrical mask found at Cataractonium (Catterick) does not necessarily confirm there was a theatre at the civil settlement, it may simply be from a theatre-goers personal collection.

Accordingly, based on the inscription, the theatre at Brough has been interpreted as indicating it was also a major settlement, possibly the civitas capital of the local tribe, the Parisi.

In Roman Britain civitas capitals were the administration centres of local level government, consisting of local people installed by the Romans to control their own tribal areas. Many of these may have originated as pre-existing Iron Age settlements; it is estimated that there were over 20 Iron Age tribal territories, of which between 11 and 16 had defined civitas capitals and awarded a tribal suffix such as Calleva [Atrebatum] (Silchester) and Venta [Belgarum] (Winchester).

However, line 8 of the inscription RIB 707 refers to Petuaria as a vicus (village) not a civitas, yet the dedication was ordered by an aedile, who maintained public buildings and was responsible for entertainment. This was a significant position, with a higher role than seems necessary for a mere `village`, hence the argument that Petuaria was the civitas capital of the Parisi. And as we have seen above the ancient geographer Ptolemy refers to Petuaria as the ‘polis’ of the Parisi.15

.jpg) |

| Petuaria Roman fort, after Halkon 2013 p.132 & Ottaway 2013 p.174 (probable line of RR2e based upon cropmarks) (Roman Roads Reseach Association) |

The limestone slab is broken along the bottom edge and on the right-hand side therefore lacking the right pelta decoration and a few letters in each line. The argument in support of civitas status follows that a letter ‘C’ apparent on the left side-panel and a letter ‘P’ on the missing right-side of the stone, has been interpreted as c(ivitas) P(arisorvm); the civitas of the Parisorum. However this interpretation has been rejected and the letter ‘C’ on the left-hand pelta said to be purely decorative.16

A vicus was a civil settlement that became established around a Roman military site, predominantly forts, as with Petuaria. There is a clear reference to ‘vici’ on the inscription and there is no evidence that Petuaria was ever granted a tribal suffix as found at other civitas capitals as noted above.

The name ‘Petuaria’ is thought to be derived from a root meaning ‘four',17 and may mean that it was the vicus of the fourth pagus, an administrative term designating a rural subdivision of a tribal territory. If this is correct it is possible that Marcus Ulpius Januarius held the position of aedile over all four subdivisions of the territory of the Parisi.

John Wacher, who excavated the site between 1958-1961, has argued that a series of characteristics contrast Brough from other civitas capitals where he sees a more military character for the site. These include the military nature of its defences and a lack of organised street system and early urban development.18

Wacher argued that that none of the excavated structures within the fortified area had parallels with domestic buildings normally found in Roman towns. He saw the site as military with an extensive naval base overlying the earlier fort. Wacher concludes that the occupation of Petuaria seems always to have been military and naval rather than civil and suggests the vicus Petuariensis may have been 3 miles downstream at North Ferribly.19

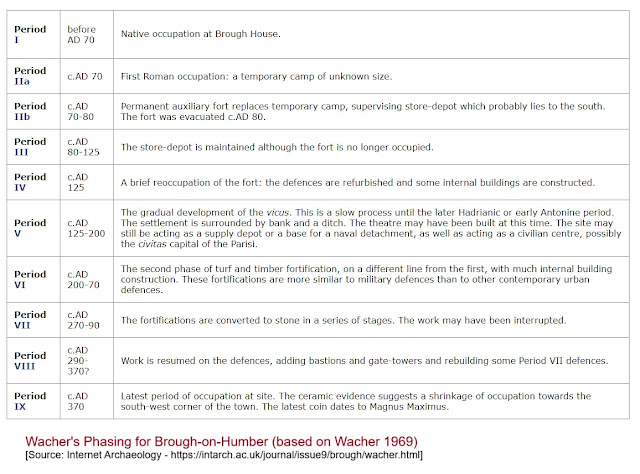

Wacher's Phasing for Brough-on-Humber20

|

Although Wacher leaned towards a purely military site with a naval port,23 the current status of the site is unresolved; the origins of Petuaria appear to begin with the Roman fort but the development of the associated vicus is unclear. It is not even certain that Brough was ever known as Peturaria Parisorum or the civitas of the Parisi. And we cannot confidently identify it from The Roman Road Itinerary Iter I.

It is significant that the stone bearing the inscription (RIB 707) was not found in its original setting where it had been erected about 140 AD but had been re-used in a 4th century building in the naval base.24 And the location of the theatre, if it was indeed ever at Brough, currently remains elusive.

The artefact assemblage is far from conclusive and the available evidence allows the site to be interpreted as a fort, a naval port and civilian settlement over sequential periods of occupation, but not necessarily in that order. It is anticipated that ongoing excavations by the Petuaria ReVisited Project will clarify the matter.

Notes & References:

1. Sheppard Frere, Britannia: A History of Roman Britain, 1967, Routledge & Kegan Paul (BCA edition, 1973), p.126.

2. Frere, p.98

3. Frere, pp.249-251

4. Frere, p.303

5. A.L.F. Rivet & Colin Smith, The Place-Names of Roman Britain, Batsford, 1979 (reprint ed. 1981), p.119.

6. Rivet & Smith, p.155-56.

7. RSO Tomlin, Numerus Supervenientium Petueriensium, pp.74-75, in JS Wacher, Excavations at Brough-on-Humber 1958- 1961, Reports of the Research Committee of the Society of Antiquaries of London No. XXV (1969).

8. Creighton 1988, pp. 401-2 – quoted by Roman Roads Research Association (RRRA), The Roads of Roman Britain, The Antonine Itinerary – Iter I

9. Rivet & Smith, 1979, p.155.

10. The Roads of Roman Britain, RRRA, The Antonine Itinerary – Iter I

11. Rivet & Smith, p.437.

12. RIB 707. Dedication to the Divine House of Antoninus Pius, Roman Inscriptions of Britain,~Roman Inscriptions of Britain

13. Frere, p.303

14. Frere, p.244

15. Rivet & Smith, p.142: Ptolemy writes"Camunlodunum [Colchester], next to whom, beside the gulf suitable for a harbour, are the Parisis and the city of Petuaria".

16. RIB 707. Dedication to the Divine House of Antoninus Pius, Roman Inscriptions of Britain,~Roman Inscriptions of Britain

17. Rivet and Smith, p.437-38: The name is a femimine of British *petuario = fourth (Welsh pedwerid, pedwyr-yd).

Compare with the Middle Welsh poem Preiddeu Annwn from the Book of Taliesin in which Arthur leads an expedition to the Welsh Otherworld to take a cauldron from “the Four-Peaked Fortress, four its revolutions” (ygkaer pedryuan, pedyr ychwelyt)

18. J.S. Wacher, Excavations at Brough-on-Humber 1958- 1961, Society of Antiquaries of London No. XXV (1969).

19. Wacher, The Towns of Roman Britain, Batsford, 1978, pp.394-97.

20. The Status of the Roman Settlement, 7.0 Discussion by K. Hunter-Mann, with D. Petts, The Roman settlement at Brough-on-Humber, Internet Archaeology.

21. Historic England Research Records: Petuaria Roman Town

22. 2481. Tile-stamps of the Auxilia: Classis Britannica, The Roman Inscriptions of Britain

23. Wacher, The Towns of Roman Britain, Batsford, 1978, p.395

24. Rivet & Smith, p.438.

* * *

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)