and Iulius, citizens of Caerlleon.” 1

The Shrines of the Holy Martyrs

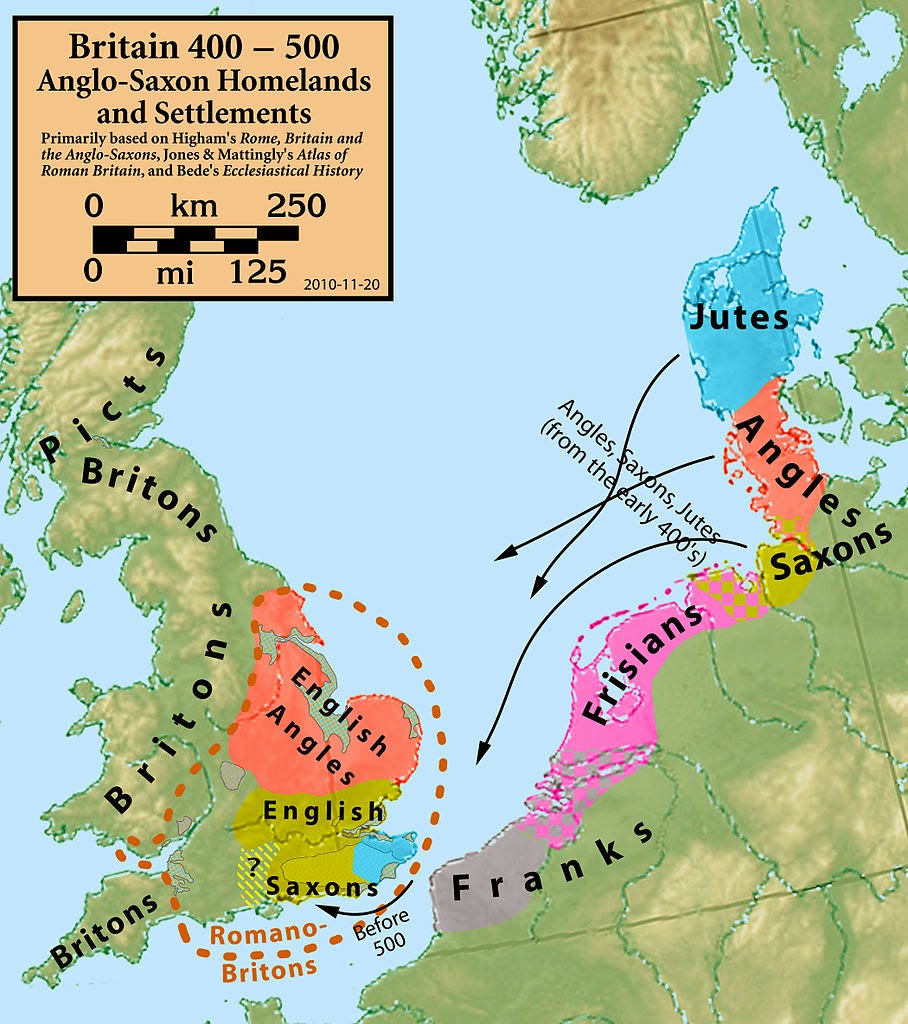

Gildas tells us that following the Roman departure from Britain the superbus tyrannus and a council of Britons employed Saxon federates to defend the Island from the threat from the Picts and Scot in the north and north-west respectively. But the federates grew in numbers and the Britons failed to supply sufficient provisions. With the foedus (treaty) broken an outbreak of violence ensued that set the island ablaze from coast to coast. The war with the Saxon federates continued up until the siege of Mons Badonicus, some 40 years before Gildas was born; thereafter an uneasy peace prevailed into his own time; so the story goes.

In Gildas' days memories of the Saxon rebellion are all but forgotten now by the generations that succeeded the kings and priests that witnessed the storm, but the cities are still not populated as they once were; he claims they are deserted, in ruins and unkempt. Gildas delivers a prophetic sermon; it seems luxuria has returned to the land and the Britons again live a life of wickedness, greed and sexual excesses; thus it seems bad times are destined to return to the island as God will again cleanse his flock.

Gildas reports in his homiletic mid-6th century De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae (On the Ruin and Conquest of Britain) 2 that external wars have stopped but civil war continues as, presumably, the Saxons remain in their territories in the east of the country? However, Gildas refers earlier (c.10) to the “unhappy partition with the barbarians” (lugubre divortium barbarorum) which deprives his fellow citizens of visiting the shrines of the holy martyrs, namely St Alban of Verulam, Aaron and Julius of Caerleon, and others in different places, all of whom he considered to have suffered during the Diocletian persecution. However, there is some doubt that the Diocletian persecutions reached Britannia; the second, third and fourth edicts of the Great Persecution do not seem to have been enforced in the West. The passio included in a Turin manuscript places St Alban's martyrdom during the time of Septimus Severus (193-211 AD), others have argued for mid-3rd century date, during the periods of the persecutions of the emperors Decius (250-1 AD) and Valerian (257-9 AD).3

The First British Christian Martyr

Gildas refers to "St Alban the man of Verulamium" which raises the question as to whether Alban was a citizen of that town or because that was were his cult was practised? According to the legend both claims are correct but Gildas seemed to lack first-hand knowledge of the site as he has Alban crossing the Thames, whose water's miraculously parted, like the Red Sea in the biblical tale, instead of the river Ver on his way to his martyrdom. All accounts are silent on the location of the martyrdom and grave, though the version in the Turin manuscript seems to perfectly match the geography of Verulamium, accurately describing the Roman town and the hill opposite across the river Ver, where the cult seems to have been focused several centuries later when St Germanus visited in the early 5th century.

|

| Roman Theatre Verulamium |

|

| Shrine of St Alban |

Verulamium seems to have been under British control into the 6th century and the martyrium of St. Alban lay in a Roman cemetery outside the city walls. It would appear nothing at the city would have prevented access to the saint's shrine; more likely something nearer Gildas' place of writing prevented him travelling to Verulamium.

The City of the Legions

The shrines of Aaron and Julius at the 'city of the legions' (urbs legionum) can only be at one of three permanent legionary fortresses in Britannia: Chester (Deva) on the river Dee in modern Cheshire; Caerleon (Isca) on the river Usk in south-east Wales; or York (Eboracum).

Gildas seems to have introduced the phrase "urbs legionum" as the term is not known as a place-name, or as a recognised description of a place, by any other writer in Roman Britain; it seems all known instances derive from Gildas. This must have been a legionary camp within his own geographic horizon known colloquially as "the city of the legions".

The identification of "the city of the legions" continues to puzzle Arthurian scholars as the site of the Dux Bellorum's ninth battle as recorded in the so-called chapter 56 of the 9th century Historia Brittonum. The author simply records the battle without further allusion to the location; presumably it was accepted the reader would know. Writing in the 12th century, Geoffrey of Monmouth had no reservation (not that he was ever shy of invention) in his Historia Regum Britanniae that "the city of the legions" was on the River Usk and the original name "Kaerusc" changed after the Romans made their winter quarters there. According to Geoffrey it had originally been the "metropolis of the Dimetia" (i.e. in The Kingdom of Dyfed, south-east Wales), near the sea of the Severn. Geoffrey, no doubt following Gildas, states this is where the shrines of Saints Aaron and Julius are located and the "deplorable impiety of barbarians deprived us of them".

|

| Roman Amphitheatre Caerleon |

A Medieval cult appears to have evolved at the site of the Roman fortress at Caerleon (Isca) for the two saints. There has been a shrine dedicated to Saints Aaron and Julius at Caerleon-on-Usk since at least the 9th century. A charter of c.864 preserved in the Liber Llan Dâv (Book of Llandaff) refers to the boundary of Merthir Julius and Aaron 'which runs along the dyke on the Usk.' The word 'Merthir' (Mythyr in Modern Welsh) is derived from the Latin 'martyrium' and also has the meaning of ‘a grave’; thus, the place-name records the district of the burial place of the saints Julius and Aaron on the south side of the river Usk. The martyrium appears to have been located within one of the three cemeteries of the Roman fortress. Around 1860 the fragment of a 9th century sculptured cross slab was found in the locality which may be evidence for the cult.

A church in Caerleon dedicated to SS. Julius and Aaron, was granted, by Robert de Chandos, to the Priory of Goldcliff, founded by him in 1113. The name of St Alban was added to the dedicatees when the church became attached to the priory which seems to have eclipsed the other two lesser known martyrs, yet the original dedication was known to the 16th century antiquary William Camden who, in describing the ruins of Isca, wrote of a house called 'St Julian's' which stood on the site of the church of St Julius the martyr, about a mile out of town. Today, a hill north-east of the modern town called 'Mount St Albans' serves as an indicator of its former existence.5

According to Butler's Saints Lives (1866) Giraldus Cambrensis claimed the bodies of SS. Julius and Aaron were honoured at Caerleon when he wrote around the year 1200. Each of these martyrs had a titular church in that city; that of St. Julius belonged to a nunnery, and that of St. Aaron to a monastery of canons. According to Bishop Godwin (1595-1601), there existed, in the recollection of the generation preceding that in which he wrote, two chapels called after Aaron and Julius, on the east and west sides of the town of Caerleon, about two miles distant from each other. The chapels deteriorated through time and were finally destroyed under Henry VIII's dissolution of the monasteries in the 16th century. However, the legend continues; in modern times a Roman Catholic church was built in Caerleon at the end of the 19th century and dedicated to SS. Aaron, Julius, and David.

|

| Church of SS Aaron, Julius and David at Caerleon |

A later Arthurian storyteller, Sir Thomas Malory also makes reference to Caerleon, notably as the site of Arthur's coronation yet he names Winchester as the site of Camelot, probably in response to Edward VI's promotion of the Hampshire county capital's Arthurian connections. However, in his preface to Malory's Le Morte D'arthur, the printer Caxton argues that Camelot is in Wales and describes the ruins of a city which sounds very much like Caerleon; “And yet of record remain in witness of him in Wales, in the town of Camelot, the great stones and the marvellous works of iron lying under the ground, and royal vaults, which divers now living have seen.”

Barbarian Partition?

Chester remained in British control until at least the Battle of Chester in 616 AD when King Æthelfrith of Northumbria massacred a combined Welsh force. Bede's account of the battle claims a large number of monks from the nearby monastery at Bangor-on-Dee who had come to pray for the British were slaughtered on the orders of Æthelfrith before the battle. Within a year of the battle Æthelfrith was dead.

The motives and significance of the battle are unclear; Bede saw the defeat of the Britons as divine retribution for the Celtic bishops refusal to join Augustine of Canterbury's mission in converting the heathen Saxons. Chester does not appear to have become 'English' as a result of the battle. Many historians see the reference to Arthur's "ninth battle...in the City of the Legion" in the Historia Brittonum as a misplaced reference to this later battle.

Archaeological excavations at Heronbridge, just south of Chester, have uncovered post-Roman graves buried beneath a defensive earthwork over an old Roman settlement. The perimortem injuries on the skeletons strongly suggests they are Northumbrian casualties from the Battle of Chester.

The Romans established a fort between the Foss and Ouse rivers around which grew up a town called Eboracum or “place of the yew trees.” Under Roman rule, York became one of the most important cities in Britannia and garrison to the legions of the north. In 306 AD, Constantine the Great, the founder of Constantinople, was declared Emperor there, an election supported by King Crocus and a large contingent of Alemanni troops.

Germanic style material culture in eastern Yorkshire has been interpreted as evidence for the settlement of Germanic people there by the late 5th century. Yet, the first Anglian king of Deira of whom we have any record is Ælla, who Bede claims was one of the kings reigning at the time of the Augustinian mission in 597. By the early 7th century, York had become an important royal centre for the Northumbrian kings with the Anglo Saxon Chronicle making first mention of Saxons at York in 627 AD when King Edwin was baptised in a wooden church there, possibly the precursor of the York Minster.

In conclusion, we must concede that Caerleon may not possess the strongest of historical claims for Gildas' 'city of the legion' but no such tradition for the obscure saints Aaron and Julius exists for either Chester or York. Further, neither Chester or York appear to have been in territories controlled by barbarians in Gildas' time of writing, c.540.

In Gildas' mind the loss of access to the martyrs' tombs was a punishment inflicted on the British because of their sins. Here again, as before, Gildas uses the barbarians as a rhetorical instrument of punishment for the moral decline of the Britons. Clearly Gildas' perception is of a barrier, political or physical, preventing pilgrims visiting the tombs of the martyrs.

>> St Alban

Copyright © 2014 Edward Watson

http://clasmerdin.blogspot.co.uk/

Notes & References

1. Hugh Williams, Gildas: The Ruin Of Britain, edited For The Hon. Society Of Cymmrodorion, 1899.

2. Gildas' time of writing De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae is dated by historians to the mid-6th century, typically c.540 AD, solely on the entry in the unreliable 10th century Welsh Annals (Annales Cambriae) which records the death of a Maelgwyn king of Gwynedd in 547 AD. It is usually accepted that Gildas' 'Maglocunus', the dragon of the island, who he names but once, was the same person and alive when he chastised him in the third part of his work, the 'Complaint' against the clergy.

3. John Crook, English Medieval Shrines, Boydell Press, 2011, pp.41-46.

4. Ibid.

5. Ibid.

* * *